Join us as we take a deep dive into Horror Game History: from where it all began to the diverse landscape of today.

Let’s be honest—horror games hit different.

They don’t just challenge your reflexes. They mess with your mind. They make you second-guess that open door, that flickering light, that sound you swear came from the hallway behind you.

And they’ve been doing it for decades.

This is your ultimate guide to the history of horror games—where they started, how they evolved, and why we keep coming back for more. From 8-bit ghosts to VR nightmares, from haunted mansions to cursed livestreams, we’re digging into every twisted corner of the genre.

Index

- Part 1: The Birth of Fear (1980s – Early 90s)

- Part 2: The Survival Horror Boom (Mid-90s – Early 2000s)

- Part 3: Genre Mutation & Mainstreaming (2004–2014)

- Part 4: The Horror Renaissance (2014–Present Day)

- Bonus: Horror Game Subgenres Explained

Part 1: The Birth of Fear (1980s – Early 90s)

Where Pixels Learned to Scream

Let’s be real—horror games didn’t start with zombies bursting through windows or cryptic fog-drenched towns. Before Resident Evil made the genre mainstream and Silent Hill turned fear into poetry, there were weird, glitchy little experiments that scared the pants off us. Or… at least made us feel a little uneasy. The roots of horror gaming are messy, primitive, and often overlooked—but they laid the groundwork for everything that followed.

So let’s rewind. Way back. Back to when games were pixel blocks, soundtracks were beeps and buzzes, and “atmosphere” meant turning the lights off and using your imagination.

📺 When Fear Was 8-Bit and Blinking

If you’re thinking horror couldn’t be scary with Atari-level graphics, you’ve clearly never played 1982’s Haunted House on the Atari 2600. You were literally a pair of floating eyeballs in a pitch-black mansion, bumping into pixelated bats and invisible enemies. It sounds silly now, sure—but at the time? It was pure stress. Limited visuals forced players to imagine the horror, and that made it worse. You couldn’t see the monster, and that made it scarier.

Sound design—if we can even call it that in the early ’80s—played a role too. Or more accurately, the lack of it.

That eerie silence, punctuated by the occasional bloop or screech, was unnerving. And hey, you try making it through a maze while the Atari’s palette flickers like a strobe and tell me you didn’t feel at least a little haunted.

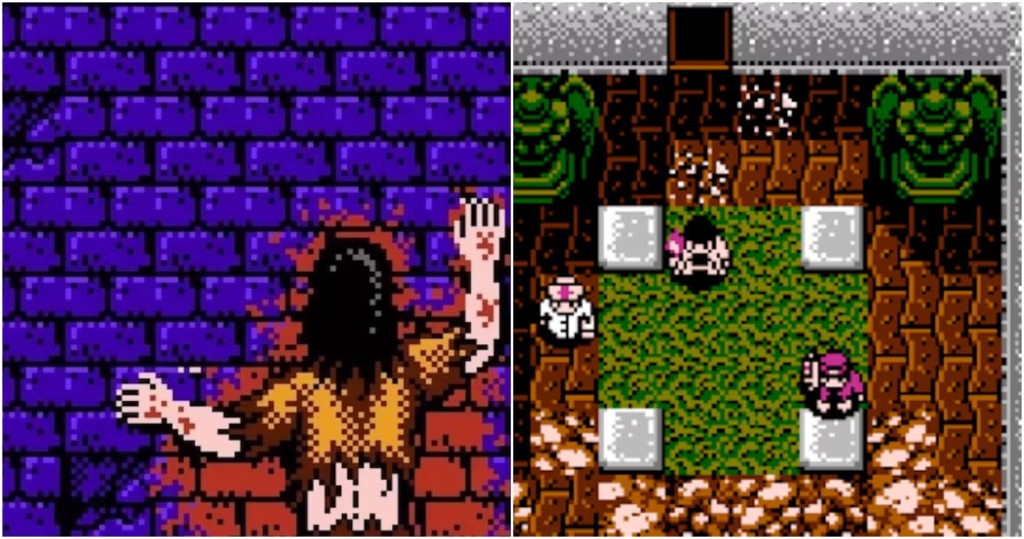

💾 Sweet Home: The Game That Actually Started It All

Ask any hardcore horror fan about the roots of survival horror and they’ll probably bring up Sweet Home. Released in 1989 for the Famicom (yep, that’s Japan’s version of the NES), Sweet Home was based on a little-known horror film by Kiyoshi Kurosawa. But unlike most film-to-game tie-ins, this one had some real teeth.

It combined RPG elements, puzzle-solving, inventory management, permadeath mechanics, and yes—a haunted mansion. Sound familiar?

If this is all giving you Resident Evil flashbacks, it should. Shinji Mikami has openly said Sweet Home was a huge influence on RE. In fact, Capcom originally planned Resident Evil as a direct remake of Sweet Home before shifting gears. The door-opening transitions, the limited item slots, even the isolated mansion full of environmental storytelling—all that started here.

And while Sweet Home never got an official Western release, the fan translation community stepped up decades later. If you’ve never played it, you can still find ROMs and translations floating around. Totally worth it—if only to see the prototype DNA of survival horror in action.

👻 Alone in the Dark (1992): 3D Terror Before 3D Was Cool

Okay, now we’re getting somewhere.

Alone in the Dark, developed by Infogrames, was a quantum leap forward—not just for horror, but for 3D gaming. Released in 1992 for MS-DOS, it placed players in a fully rendered 3D environment, complete with fixed camera angles and polygonal nightmares. The main character moved with stiff, tank-like controls, and combat felt… well, clunky at best. But you know what? That awkwardness added to the fear. You couldn’t just run. You had to commit to every movement.

The game was drenched in Lovecraftian weirdness—eldritch monsters, reanimated corpses, and a cursed mansion that felt like it was alive. The plot had actual depth (a rarity at the time), and the puzzles weren’t just “use key on door” level easy—they had logic. Real logic.

Alone in the Dark didn’t just set the mood—it defined the blueprint that Resident Evil would famously refine four years later. It’s no exaggeration to say this game walked so survival horror could sprint, stumble, and eventually explode into mainstream culture.

🧠 Hardware Limitations = Creative Horror

Here’s the thing about early horror games: they didn’t scare you with high-end graphics or orchestral stings. They scared you by making your brain do the work. Developers were forced to lean on suggestion, pacing, and discomfort—not gore or shock value. Kind of like old radio horror dramas, where the scariest part was the stuff you didn’t hear.

Consider this: Sweet Home used a menu to show character injury states. “Your character is vomiting.” Not a flashy animation. Just text. But that somehow hits harder, doesn’t it?

This is the era where:

- Static images and sudden stings replaced full-motion cutscenes.

- Music was more about what wasn’t playing than what was.

- Glitches sometimes became part of the horror (intentionally or not).

It’s no accident that indie horror games today—like World of Horror or Faith—often pull from this same low-fi aesthetic. There’s something timeless about horror that whispers instead of screams.

🎬 Horror Films Cast a Long, Creepy Shadow

Let’s not pretend games existed in a vacuum. The ’80s were a golden age for horror cinema, and those influences bled right into early games. Friday the 13th, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, and Halloween all got game adaptations—some charming, others flat-out bizarre.

Friday the 13th on NES (1989) is legendary, mostly for how confusing it was. Jason would just show up, murder everyone, and vanish. The game’s jarring music loops and awkward jump-scares created something weirdly unnerving—even if it wasn’t… you know… good. It still left an impression.

Games were absorbing horror’s tropes—masked killers, haunted mansions, helpless protagonists—and learning how to make them interactive. Even the slasher genre’s pacing (slow build-ups, sudden violence, final confrontations) began influencing game structure.

🗾 Japan’s Early Influence Was Subtle But Powerful

While the West was busy adapting horror flicks, Japanese devs were quietly laying the emotional groundwork for psychological horror. Sweet Home was only part of it.

Games like Laplace no Ma (a 1987 Japanese-only RPG based on tabletop horror campaigns) and early Shin Megami Tensei entries tackled darker, existential themes. They didn’t just go for gore—they explored things like cults, possession, and the unraveling of sanity.

There was a quiet elegance in how Japanese horror approached fear. Less “boogeyman jumps out of closet,” more “you’ve always lived in this nightmare, you just forgot.” That sensibility would explode later with Silent Hill—but even here, in the early ’90s, the seeds were planted.

🔍 The Horror Wasn’t Always Labelled

One odd thing about this early era? We didn’t really call these games “horror games.” That label hadn’t stuck yet. Players just called them “adventure games” or “creepy RPGs” or “that weird game where you walk around a mansion.”

It wasn’t until Resident Evil hit in 1996—proudly bearing the “survival horror” label in its marketing—that we got a genre name to rally around. Before that, horror in games was more like a vibe than a category. But it was there, hiding in the shadows of dusty cartridges and DOS prompts.

🧠 Looking Back: Why It Still Works

The funny thing? Go back and play these games now—Haunted House, Sweet Home, Alone in the Dark—and you might still get chills. Not because they hold up graphically (they don’t), or because they’re particularly smooth (they’re not). But because they understood something modern games sometimes forget:

Fear lives in the unknown.

In the loading screen that lingers a little too long.

In the silence between beeps.

In the thing you think is behind you, even though nothing’s there.

🧠 TL;DR – Key Moments in Early Horror Gaming

If you’re a bullet-point kind of reader, here’s a snapshot of what defined horror gaming’s earliest era:

- 1982 – Haunted House (Atari 2600): Early experiment with darkness and tension.

- 1989 – Sweet Home (Famicom): Survival horror roots, inventory systems, permadeath.

- 1992 – Alone in the Dark (PC): 3D horror with fixed camera angles and Lovecraftian themes.

- Late ’80s – Movie tie-ins (Friday the 13th, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre): Not great, but influential.

- Early Japanese titles – Laplace no Ma, early Megami Tensei games: Foundations of psychological horror.

- Emerging tropes: Haunted mansions, limited visibility, fear through suggestion.

Part 2: The Survival Horror Boom (Mid-90s – Early 2000s)

Fixed Cameras, Tank Controls, and Trauma

By the mid-1990s, horror games had finally found their heartbeat—though it usually sounded like a low, distorted thump echoing through an empty hallway.

This was the era that coined the term “survival horror.” It was when developers stopped flirting with fear and decided to marry it, awkward camera angles and all. Games were no longer just “creepy”; they were designed to make you sweat.

And while some of that tension came from the monsters, a lot of it came from you—the player—fumbling for the right key, watching your last bullet vanish into the shadows, and realising too late that you forgot to save.

🎮 The Game That Named the Genre: Resident Evil (1996)

Let’s not bury the lead—Resident Evil changed everything.

When Capcom dropped Biohazard (its Japanese title) in 1996, most gamers didn’t know what hit them. Set in a crumbling mansion filled with undead, rabid dogs, weird statues, and vaguely occult vibes, it wasn’t just a horror game—it was horror. Claustrophobic. Slow. Stressful. Brutally punishing in the best way.

It had:

- Tank controls that made every movement feel like a commitment.

- Fixed camera angles that robbed you of control and framed tension like a cinematic shot.

- Scarce resources, forcing real decisions: fight or flee?

- And yes—that moment with the zombie turning its head in the hallway. You know the one.

The phrase “survival horror” was printed right on the packaging. Marketing term? Sure. But it stuck. It gave us a language for a whole new kind of experience.

And Resident Evil didn’t just spark a genre—it ignited a franchise. By the time RE2 dropped in 1998, the series had already become a cultural juggernaut. Bigger environments. More story. Dual protagonists. Lickers. That creepy music in the RPD hallways. It all just worked.

Want to revisit that golden era? Capcom’s official Resident Evil portal is a nostalgia machine.

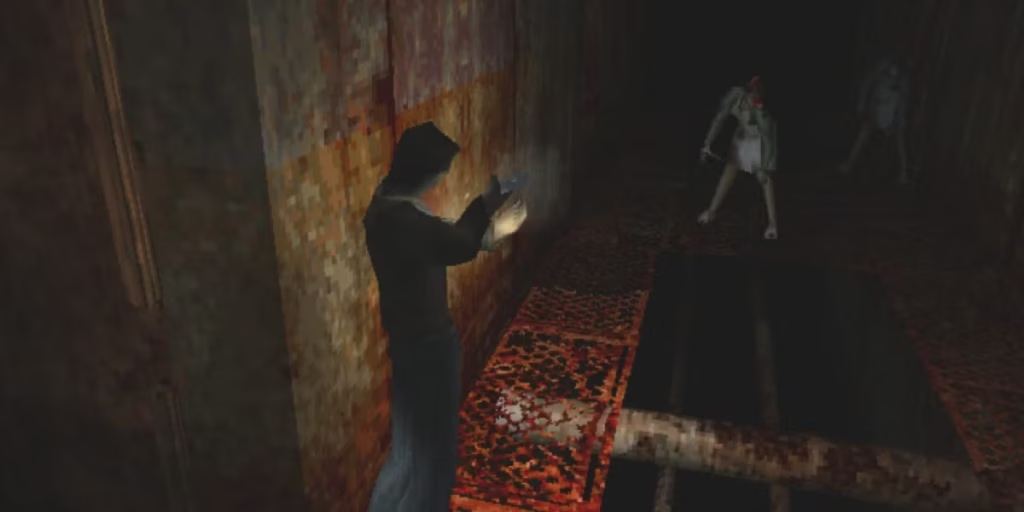

🔥 Silent Hill (1999): Fear With a Soul

If Resident Evil was about survival, Silent Hill was about suffering.

Konami’s masterpiece wasn’t content to scare you with jump scares or gore (though it had those, too). It wanted to get under your skin—emotionally, psychologically. Its fog-drenched streets weren’t just eerie; they were metaphors for trauma. The monsters weren’t just creepy—they were your guilt, fear, and repressed memory made flesh.

Where Resident Evil pulled from Western horror cinema—Romero, Carpenter, Fulci—Silent Hill was drenched in psychological dread and arthouse influence. Think Jacob’s Ladder, Eraserhead, even David Lynch at his most unhinged.

And let’s not forget that soundtrack. Akira Yamaoka’s industrial-ambient nightmare fuel turned static into a source of genuine panic. Even silence had weight.

Silent Hill wasn’t easy. It didn’t care if you were confused. That was the point. It asked players to feel lost, helpless, and disoriented—and somehow made that experience beautiful.

📼 Tank Controls and Fixed Cameras: Love ’Em or Hate ’Em?

Look, we can’t talk about this era without talking about tank controls. Yes, they were clunky. Yes, turning your character sometimes felt like steering a boat with a broken rudder. But here’s the thing—they worked in horror.

Why? Because they made you vulnerable. And in horror, vulnerability is everything.

Same goes for fixed camera angles. Sure, they were a technical limitation—but they were also brilliant for building tension. You’d hear footsteps, but couldn’t see where they were coming from. You’d walk into a room and the camera would shift, framing you from a low angle like a horror movie shot. It created dread without needing fancy effects.

Games like Resident Evil and Clock Tower leaned hard into these quirks. And while newer fans might laugh at them now, they were absolutely part of what made these games so iconic.

📷 Clock Tower, Fatal Frame & The Rise of Horror Heroines

During this golden age, horror also began experimenting with helplessness as a mechanic. Enter: Clock Tower (1995).

Instead of giving you a gun, Clock Tower gave you a stalker. A literal one. Scissorman, with his oversized shears and slow shuffle, could appear at random—and your only defense was hiding. Under a desk. In a closet. Wherever.

The tension? Real.

Then came Fatal Frame (2001), known in Japan as Project Zero. Another female lead, another twist: instead of fighting ghosts with weapons, you had a camera. The “Camera Obscura” let you exorcise spirits by photographing them as they lunged toward you.

And yeah—it was just as terrifying as it sounds.

These games gave us:

- Vulnerable protagonists (often women)

- Haunting atmosphere over raw gore

- Deep ties to folklore, trauma, and memory

- Unique mechanics that enhanced the fear

They were quiet, slow-burning nightmares—and absolutely vital to the genre’s DNA.

🧬 Horror Starts Splintering: Bio-Sci-Fi, Occult, and Experimental

While RE and Silent Hill dominated the spotlight, other studios were cooking up their own takes on horror.

- Dino Crisis (1999): Capcom again, but with dinosaurs instead of zombies. Same fixed cameras, same puzzle-driven tension—but more Jurassic Park than Romero.

- System Shock 2 (1999): FPS-meets-survival horror in deep space. A masterclass in environmental storytelling and dread.

- The Suffering (2004): A lesser-known gem that fused psychological horror with brutal combat in a haunted prison.

This era saw horror branching out:

- From haunted houses to abandoned space stations

- From slow burn to action-infused terror

- From flesh-and-blood monsters to hallucinations and existential dread

Horror was expanding—but it was still raw. Still unfiltered.

🎥 Cutscenes and Cinematic Horror Arrive

Another shift happened during this time—games started getting cinematic.

Thanks to CD-ROMs and better hardware, developers could include full-motion video (FMV), longer cutscenes, and voice acting. Granted, some of it was hilariously bad (looking at you, original Resident Evil voiceovers), but the ambition was there.

These weren’t just “levels” anymore—they were stories. And the more horror leaned into story, the more emotionally invested players became.

We weren’t just scared for our characters—we were scared as them.

🔄 Replay Value and the Birth of Branching Horror

Let’s give a quick shoutout to one underrated innovation of this era: multiple endings.

Games like Resident Evil, Silent Hill, and Clock Tower began experimenting with player choice, often subtly. Heal a certain character, use a specific item, or visit a hidden location, and the game would remember. You’d unlock a different ending—sometimes hopeful, sometimes bleak, sometimes… weird.

It wasn’t just a gimmick. It made you want to replay the game. To see what you missed. To obsess over every detail, every hallway, every piece of scattered lore.

🧠 Why This Era Still Haunts Us

So why does this period of horror gaming still feel so powerful?

It’s not just nostalgia (though, let’s be honest, that’s part of it). It’s because this was the moment horror matured. It stopped being a novelty and became a genre. A serious one.

These games weren’t just scary. They were artful. Thoughtful. Sometimes messy, sometimes clunky—but always aiming for something. And that ambition gave them staying power.

You can remake a game a thousand times (RE2make, SH2 Remake—we see you), but that first time you walked into that fog, or pushed open that creaky door? You don’t forget that.

🕹️ Quick Reference: The Icons of This Era

Here’s your cheat sheet—some key titles and why they mattered:

- Resident Evil (1996) – The template for survival horror. Scarcity, tension, and that mansion.

- Silent Hill (1999) – Psychological dread. Storytelling with emotional depth and fog.

- Clock Tower (1995) – Introduced helplessness as horror. Random enemy encounters kept you sweating.

- Fatal Frame (2001) – Ghosts and a camera. Haunting, elegant, and painfully underrated.

- System Shock 2 (1999) – Survival horror meets sci-fi immersion.

- Dino Crisis (1999) – Action-horror with dinosaurs. Yes, it was awesome.

- The Suffering (2004) – A grungy, gory mind-trip through personal demons and prison hellscapes.

🧠 Part 3: Genre Mutation & Mainstreaming (2004–2014)

When Horror Got Guns—And Almost Lost Its Soul

So here’s the thing: horror didn’t die in the 2000s. But it did… change. A lot.

Following the massive success of Resident Evil, Silent Hill, and other late-’90s trailblazers, horror games started getting bigger. Louder. Flashier. Studios wanted more action, more spectacle—sometimes at the cost of actual fear.

This wasn’t always a bad thing. Some of the best horror experiences came from this era. But the genre itself? It splintered. Some games doubled down on combat. Others chased psychological complexity. And in the shadows, something new was growing—tiny indie projects, experimenting with fear in ways AAA games couldn’t (or wouldn’t).

Let’s break it down.

🎮 Resident Evil 4 (2005): The Game-Changer (Literally)

Let’s get this out of the way: Resident Evil 4 is one of the most influential games of all time.

It completely reinvented the franchise—and arguably the third-person shooter genre—with its over-the-shoulder camera, tight combat, and relentless pacing. Leon Kennedy wasn’t slowly stumbling through a haunted mansion anymore. He was roundhouse-kicking parasites in rural Spain and suplexing cultists like it was a WWE crossover.

It was tense. It was brilliant. It was terrifying in a totally different way.

But here’s the catch: RE4 shifted the entire series—and the genre—away from classic survival horror and toward something more action-driven. Ammo was plentiful. Enemies were faster, smarter, and everywhere. The eerie quiet of earlier titles gave way to cinematic set-pieces and explosive shootouts.

Some fans loved the evolution. Others mourned what was lost.

🎭 Silent Hill Struggles in the Fog

While Resident Evil was evolving, Silent Hill… well, it kind of stumbled.

Silent Hill 2 (2001) was still fresh in gamers’ minds—a haunting masterpiece of emotion, dread, and guilt. But the sequels that followed (SH3, SH4, and especially Homecoming and Downpour) didn’t quite hit the same emotional notes.

Was it the Western development studios taking over? Was it fatigue? Was it just bad luck?

Whatever the reason, Silent Hill struggled to maintain its identity. The psychological layers remained, but the gameplay started to feel muddled—caught between preserving its quiet terror and chasing the more kinetic style of its competitors.

That said, even the weaker entries had moments. Silent Hill 4’s apartment hub slowly morphing into a personal prison? Still creepy. Downpour’s dynamic weather system? Interesting idea, just not fully baked.

And of course, there’s Shattered Memories—an oddball reimagining of the original game that swapped combat for psychological profiling. You literally took a personality test that shaped the game’s monsters and characters. Bold? Absolutely. Scary? Debatable. But it showed Konami was still willing to take risks… sometimes.

👽 The Rise of Sci-Fi Horror: Dead Space (2008)

If Resident Evil 4 brought action to horror, Dead Space perfected the balance.

Set aboard a derelict space mining ship infested with mutated horrors, Dead Space gave us:

- Zero HUD immersion (your health was on your suit!)

- Dismemberment-focused combat

- Creeping dread that built over hours

- And sound design so good it practically required a therapy session

Isaac Clarke wasn’t just blasting aliens—he was unraveling mentally, piece by piece. The game leaned hard into body horror and isolation, giving us an experience that felt equal parts Alien and The Thing.

It was cinematic. Brutal. And, somehow, still terrifying—even as you became more powerful.

Dead Space 2 (2011) cranked things up with more action and tighter pacing. And while Dead Space 3 leaned a little too far into co-op gunplay (read: shoot everything that moves), the franchise had already carved its place into horror history.

🧟 Resident Evil 5 & 6: The Identity Crisis

Then came Resident Evil 5. And Resident Evil 6. And… yeah.

Let’s not sugarcoat it: by this point, Resident Evil had become an action blockbuster. RE5 traded scares for boulder-punching absurdity, and RE6 was a Frankenstein’s monster of genres—four overlapping campaigns, QTEs galore, and explosions that would make Michael Bay blush.

Was it fun? Sometimes. Was it horror? Not really.

Capcom later admitted it had lost sight of what Resident Evil was supposed to be. And honestly? Players noticed. The franchise didn’t feel like horror anymore. It felt like a third-person shooter with zombies as set dressing.

The soul was missing. But that would change—just not yet.

🕹️ The Indie Whispers Begin: Penumbra & Amnesia

While the big-budget titles were going big, a small studio in Sweden called Frictional Games was quietly doing the opposite.

Penumbra (2007) was one of the first games to use physics-based puzzles and real-time object interaction to immerse players. You didn’t just press a button to open a door—you grabbed it, dragged it open, peeked through. It felt real, and it made every encounter more intense.

Then came Amnesia: The Dark Descent (2010), and everything changed.

No weapons. No combat. No HUD. Just a man, a lantern, and his sanity slowly unraveling in a castle full of unspeakable horrors.

It was revolutionary. You had to hide. To run. To not look directly at the monsters because even seeing them could drive your character insane.

Let me repeat that: seeing the monster was bad for your brain.

Amnesia became a cultural moment. Streamers, YouTubers, and horror fans devoured it. It proved that horror didn’t need big budgets to be effective—it needed atmosphere, sound design, and a willingness to make the player feel helpless.

And it laid the groundwork for the indie horror explosion to come.

🧠 Horror Gets Smart (And Sometimes Pretentious)

This era also saw horror trying to mean more. Games started to explore trauma, mental illness, and personal demons—not just jump scares and gore.

A few notables:

- Rule of Rose (2006): A controversial cult classic about childhood trauma, repressed memories, and emotional abuse.

- Pathologic (2005): A Russian plague survival sim that felt like an anxiety dream you couldn’t wake up from.

- Condemned: Criminal Origins (2005): Psychological horror wrapped in first-person melee combat. Grimy, brutal, unforgettable.

These games weren’t always “fun” in the traditional sense. But they left a mark. They asked questions. They lingered.

🎥 YouTube Horror & the Birth of the Let’s Play Scare

Here’s a twist no one saw coming: by the early 2010s, YouTube was quietly reshaping horror.

Streamers and content creators—PewDiePie, Markiplier, Jacksepticeye—began uploading Let’s Plays of horror games. Suddenly, horror wasn’t just something you played. It was something you watched. Laughed at. Screamed with.

Games like Slender: The Eight Pages (2012) and Five Nights at Freddy’s (2014) exploded because of this. They were built for reactions—short, punchy, terrifying experiences that looked great on camera and made for viral content.

Critics scoffed. Fans screamed. And indie devs saw an opportunity.

🧩 The Genre Splinters: Horror Subtypes Emerge

By 2014, horror had become… well, lots of things. The clean genre lines of the late ’90s were long gone. Instead, horror had branched into multiple flavors:

- Action Horror: Think RE4, Dead Space, The Evil Within

- Psychological Horror: Silent Hill, Amnesia, Rule of Rose

- Survival Horror: Project Zomboid, Darkwood, DayZ

- Walking Sim Horror: Layers of Fear, The Vanishing of Ethan Carter

- Stealth Horror: Hello Neighbor, Alien: Isolation

- Viral Horror: Slender, FNaF, Baldi’s Basics

No single style dominated. Horror had become a buffet. Some fans missed the old-school tension. Others embraced the new weirdness. Either way, horror was more alive—and more fractured—than ever.

🧠 Why This Era Mattered

The 2004–2014 period was messy. Bold. Confused. It gave us brilliance and garbage, sometimes in the same game. But that chaos was necessary.

This was horror stretching its legs. Figuring out what it could be. Exploring what scared people in a world where players were becoming harder to frighten.

We saw:

- The rise and fall of AAA horror

- The birth of indie horror as a cultural force

- The integration of player psychology and story

- The beginning of community-driven horror experiences

It wasn’t always great. But it was important. It opened the door for what came next.

🕹️ Snapshot: 10 Standout Titles from the Era

- Resident Evil 4 (2005): Action-horror perfection

- Silent Hill 4 (2004): The end of an era

- Fatal Frame 2 (2003): Elegant and terrifying

- Dead Space (2008): Sci-fi horror masterclass

- Amnesia: The Dark Descent (2010): Indie terror landmark

- Slender: The Eight Pages (2012): Viral horror 101

- F.E.A.R. (2005): Paranormal shooter with incredible AI

- Condemned: Criminal Origins (2005): Gritty, violent, unnerving

- The Evil Within (2014): Shinji Mikami’s horror return

- Five Nights at Freddy’s (2014): Love it or hate it, it changed the game

🧨 Part 4: The Horror Renaissance (2014–Present Day)

Streamers, Screams, and a New Golden Age

Let’s be honest—by the early 2010s, horror games were looking a little lost. Big franchises like Resident Evil had drifted into overblown action. Silent Hill was basically wheezing its last breath. Even the indie scene was starting to feel formulaic, with jump scare-fueled YouTube bait dominating the conversation.

And then… something changed.

Quietly at first, then all at once, horror came home. Developers, streamers, and players reconnected with the soul of the genre. The result? A full-blown renaissance. Gritty, raw, emotionally charged, often experimental—and sometimes just plain fun.

This isn’t just a comeback. It’s a rebirth.

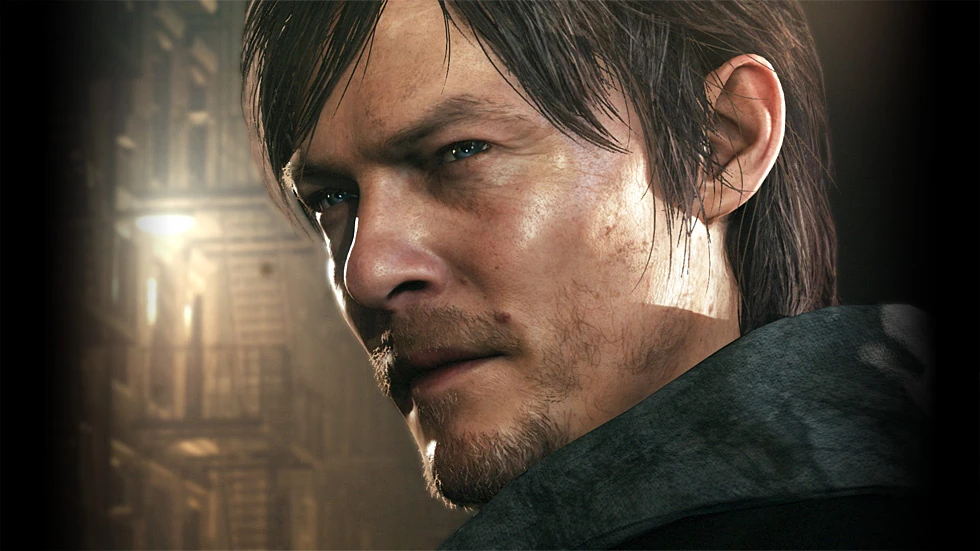

🎭 P.T. (2014): The Ghost That Still Haunts Us

No horror timeline would be complete without P.T.—the “playable teaser” that became a full-on phenomenon. Dropped onto the PlayStation Store by surprise in 2014, it came with no fanfare, no context, and a completely generic publisher name: “7780s Studio.”

But those who downloaded it? Yeah, they were never the same again…

What started as a hallway loop quickly devolved into one of the most terrifying, layered, and brain-melting experiences ever built in a game engine. You weren’t fighting monsters. You were trapped in a psychological maze. It was about subtle shifts, audio illusions, spatial loops, and that one radio broadcast that just shouldn’t be there.

Then came the reveal—P.T. was secretly a demo for Silent Hills, a project helmed by Hideo Kojima, Guillermo del Toro, and Norman Reedus.

And then… Konami canceled it.

No joke, that cancellation might be one of the biggest heartbreaks in horror game history. But P.T. didn’t just fade away. It sparked a movement. Developers took note. Fans obsessed over it. And to this day, it’s still getting remade, referenced, and revered like some lost religious text.

🧪 Resident Evil Finds Its Fear Again: RE7 & RE: Village

After RE6 went full Hollywood, Capcom hit the brakes—and turned off the lights.

Resident Evil 7: Biohazard (2017) brought the franchise screaming back to its survival horror roots… with a first-person twist. Gone were the global conspiracies and jet-ski chases. This was a single house. A single night. A single family of cannibals straight out of a Southern Gothic nightmare.

It worked. RE7 was intimate, brutal, and genuinely terrifying. It understood that horror is smaller than action. It’s in the creaking floorboard. The whispered threat. The VHS tape that plays just a second too long.

Then came Resident Evil Village (2021). Bigger, yes—but still scary. It leaned into gothic horror tropes: werewolves, vampires, Eastern European ruins. And while not quite as tense as RE7, it hit a rare balance between pulp and panic. Plus… Lady Dimitrescu. Enough said.

These games didn’t just revive the series—they reminded everyone why Resident Evil mattered in the first place.

Explore Capcom’s RE legacy here: https://www.residentevil.com

🎮 Indie Horror Explodes: Small Teams, Big Screams

Here’s where things get interesting.

With tools like Unity, Unreal, and RPG Maker becoming accessible to nearly anyone, indie horror absolutely exploded. Suddenly, small dev teams—or solo creators—were building nightmare-fuel faster than the big studios could keep up.

And they weren’t just copying Amnesia or P.T.—they were doing weirder, more personal stuff. Games that played with aesthetics, formats, mechanics, and even reality.

Some standout titles:

- Faith (Airdorf): An exorcism-themed horror game made in Apple II-style pixel art. Somehow terrifying.

- World of Horror (panstasz): Lovecraft meets Junji Ito in a retro RPG format.

- Doki Doki Literature Club: Starts as a cutesy dating sim, ends with existential dread and code-level horror.

- Signalis (2022): A PS1-style, sci-fi survival horror with one of the most emotionally devastating endings of the decade.

- Iron Lung (David Szymanski): A one-room sub-sim horror game that’s about looking at the wrong time.

These games weren’t afraid to be strange. And they didn’t need massive budgets to be terrifying. What they needed—what they had—was vision.

🧟 The Rise of Co-op and Social Horror

But horror wasn’t just getting weirder—it was getting social. Multiplayer horror, once a niche concept, suddenly became one of the genre’s hottest trends.

- Phasmophobia (2020): Four players, one haunted house, zero guarantees. It turns ghost hunting into a whisper-filled panic fest.

- Lethal Company (2023): Darkly hilarious co-op horror about salvaging junk on creepy moons—until someone gets dragged screaming into a ceiling vent.

- Devour / Pacify: Small-team survival against increasingly aggressive supernatural entities.

- Dead by Daylight: Asymmetrical horror perfected—one killer, four survivors, endless DLC crossovers from Scream to Stranger Things.

These games shifted the vibe from solitary fear to shared fear. And in doing so, they created entirely new forms of tension—now it wasn’t just you versus the monster. It was you versus the panic of your teammates, the betrayal of bad decisions, the chaos of being watched live.

📹 Streaming Changed the Game (Literally)

Let’s not ignore the elephant in the haunted room: Twitch and YouTube made horror watchable.

You know what? Horror + audience reaction = gold.

Whether it was FNaF jump-scares, Amnesia panic flails, or P.T. unraveling someone’s mental health in real-time, horror games became a performance.

Some devs even design with streaming in mind now:

- Loud sound cues for big reactions

- Short sessions for shareable content

- Replayable randomness to keep things fresh

Is it purist horror? Not always. But it’s effective—and more importantly, it’s fun.

🧠 Experimental Horror Is Thriving

Modern horror isn’t just about scares anymore—it’s about concepts. About narrative form. About player psychology. This is where it gets juicy.

- Inscryption: A card game that slowly devolves into ARG-infused meta-horror.

- Stories Untold: Retro text-based interfaces turned into sinister puzzle pieces.

- The Mortuary Assistant: You embalm bodies—and occasionally get possessed. It’s about grief as much as ghosts.

- Darkwood: Top-down survival horror that somehow feels more immersive than most FPS games.

These games mess with structure, expectations, and genre boundaries. They’re not just about running or hiding—they’re about thinking. And feeling.

🧬 Horror Tech: VR, PS5, and the Return of Texture

Let’s get technical for a second.

As game engines get more advanced, horror benefits more than most genres. Why?

Because horror lives in the details. In the lighting. The ambient sound. The subtle animations. And right now, tech is catching up with horror’s ambitions.

- VR Horror is more intense than ever (RE7 in VR is unreasonably terrifying)

- Haptics (on PS5, for example) let you feel the heartbeat of your character—or the slam of something on the other side of the wall.

- 3D audio places whispers behind you even when you’re wearing headphones. And you will look behind you.

It’s not just about looking good—it’s about building presence. And presence, in horror, is everything.

🗃️ Horror Subgenres Now (2024 Snapshot)

At this point, horror is a multiverse. Here’s a quick-glance look at what the genre looks like today:

- Retro Horror: Faith, World of Horror, Signalis

- Co-op Horror: Phasmophobia, Lethal Company, Devour

- Story-Driven Horror: The Mortuary Assistant, Oxenfree, Until Dawn

- Experimental / Meta Horror: Inscryption, Doki Doki Literature Club, Stories Untold

- VR Horror: RE7 VR, Cosmodread, Propagation VR

- Classic Survival Horror (Resurrected): RE2 Remake, Dead Space Remake, Tormented Souls

The beauty? There’s something for everyone. Whether you like cerebral weirdness, cheap thrills, or straight-up existential despair—you’re covered.

🧠 Why Horror Keeps Coming Back

So why does horror survive? Why does it keep reinventing itself when other genres fade or collapse under trend fatigue?

Because horror is primal. It adapts.

- As tech improves, horror gets more immersive.

- As culture shifts, horror reflects our fears.

- As players mature, horror deepens.

It’s personal. It’s emotional. It matters.

And in a world where attention spans are short and stories are disposable, horror dares to linger.

🕹️ The Modern Greats: A Quick Reference List

Here’s your cheat sheet for modern horror must-plays:

- Resident Evil 7 & Village (Capcom)

- P.T. (Silent ghost of greatness)

- Amnesia: Rebirth (Frictional Games)

- Phasmophobia (Kinetic Games)

- Signalis (Rose-engine)

- World of Horror (panstasz)

- Inscryption (Daniel Mullins Games)

- The Mortuary Assistant (DarkStone Digital)

- Lethal Company (Zeekerss)

- Iron Lung (David Szymanski)

Each one is doing something different. And that’s the point.

What Comes Next?

We’re already seeing horror move in new directions:

- Procedural storytelling

- AI-driven fear responses

- More personal narratives (grief, trauma, memory)

- Horror as therapy, not just adrenaline

Maybe the scariest thing is how limitless it all feels now.

💀 Epilogue: Horror Never Dies

We’ve come a long way—from pixelated haunted houses on the Atari, to PS1 tank controls, to VR seances and Twitch scream-fests. Horror has aged, evolved, and fractured—but it never left.

It adapted. It grew teeth. And then it smiled.

This is the genre that refuses to fade. Because no matter the era, no matter the medium…

We always want to be scared.

🧩 Bonus: Horror Game Subgenres Explained

A Bloody Breakdown of What Scares Us (and Why)

If you’ve made it this far in the guide, you’ve probably noticed something: horror games aren’t one thing.

They’re dozens of things.

Sometimes you’re hiding in a closet with no weapon. Sometimes you’re gunning down necromorphs with a plasma cutter. And sometimes you’re just… standing there. Questioning your reality.

So let’s break down the flavors of fear—because understanding horror subgenres is like learning the difference between a ghost story and a slasher film. It’s all horror, sure. But the vibes? Very different.

🧟♂️ Survival Horror

Core Idea: Scarcity, isolation, and just enough tools to maybe make it out alive.

Hallmarks:

- Limited ammo, health, and saves

- Inventory management

- Puzzle-solving

- Emphasis on avoidance or smart combat

Key Games:

Why It Works: Survival horror preys on resource anxiety. You’re not a hero—you’re barely hanging on. Every bullet matters. Every door could be your last.

🧠 Psychological Horror

Core Idea: The monsters aren’t just outside—you brought some with you.

Hallmarks:

- Unreliable narrators

- Distorted environments and logic

- Themes of trauma, guilt, or memory

- Minimal combat, often story-heavy

Key Games:

Why It Works: This flavor of horror doesn’t always show its teeth. Instead, it makes you feel off. The fear is slow. Creeping. Personal.

Check out our list of the best Psychological horror games available in 2025.

💥 Action Horror

Core Idea: You can fight back—but that doesn’t mean you’re safe.

Hallmarks:

- Fluid combat systems

- Larger enemy waves

- Horror atmosphere mixed with fast pacing

- Inventory and crafting systems

Key Games:

Why It Works: Action horror lets you feel powerful, then rips it away just enough to keep you scared. It walks a tightrope between adrenaline and dread.

👻 Atmospheric / Walking Sim Horror

Core Idea: Slow pacing, deep worldbuilding, and fear through immersion.

Hallmarks:

- Exploration over combat

- Narrative-driven design

- Environmental storytelling

- Audio and visual tension

Key Games:

- Layers of Fear

- What Remains of Edith Finch (light horror vibes)

- The Vanishing of Ethan Carter

- Observer

- Stories Untold

Why It Works: These games don’t always attack you. They sit with you. They build dread slowly, like fog rolling in—and leave you thinking about them long after the credits roll.

🎮 Multiplayer / Co-op Horror

Core Idea: Fear is worse when it’s shared—and your friends aren’t always helpful.

Hallmarks:

- 1v4 or team-based gameplay

- Communication-focused mechanics

- Cooperative objectives under stress

- Randomized scares and procedural elements

Key Games:

Why It Works: When you’re laughing and screaming with others, fear becomes a dynamic experience. It’s not about AI—it’s about chaos, teamwork, and that one friend who always opens the wrong door.

🕹️ Roguelike / Permadeath Horror

Core Idea: Fear + failure = replay.

Hallmarks:

- Randomized environments

- High-stakes death (often permanent)

- Limited visibility or knowledge on each run

- Progress through pattern recognition

Key Games:

Why It Works: You don’t just fear the monster—you fear the reset. Knowing that one mistake could erase your progress makes every encounter intense.

🖥️ Retro / VHS Horror

Core Idea: Lo-fi aesthetics, high-anxiety tension.

Hallmarks:

- PS1-style graphics or pixel art

- Analog distortion and CRT-style interfaces

- Limited controls or “deliberate jank”

- Minimal exposition

Key Games:

Why It Works: There’s something wrong about lo-fi horror. Maybe it’s nostalgia gone sour. Maybe it’s the fuzziness of memory. But the blur makes it worse—you can’t quite see what’s hunting you, and that’s the point.

🧪 Experimental / Meta Horror

Core Idea: Horror that breaks rules—and sometimes breaks you.

Hallmarks:

- Fourth-wall breaking mechanics

- ARG elements or real-world crossover

- Narrative twists that subvert expectations

- Interface manipulation, save file corruption, in-game “glitches”

Key Games:

- Inscryption

- Doki Doki Literature Club

- There Is No Game: Wrong Dimension

- Stories Untold

- Buddy Simulator 1984

Why It Works: This subgenre turns curiosity into paranoia. When the game starts responding to you, not just your character, the line between fiction and reality gets razor-thin.

🎯 Which Subgenre Is Right for You?

Horror is deeply personal. Some players chase the feeling of helplessness. Others want tension with teeth. So if you’re just starting your horror journey—or building your backlog—here’s a quick nudge in the right direction:

- Want classic dread and strategy? Start with Resident Evil 2 Remake.

- Craving psychological depth? Silent Hill 2 or Signalis.

- Prefer a social experience? Try Phasmophobia or Lethal Company with friends.

- Love story-rich, minimal combat games? Go for The Mortuary Assistant or Layers of Fear.

- Need a weird, meta ride? Buckle up for Inscryption.

Final Thoughts: Horror Isn’t a Genre—It’s a Feeling

At the end of the day, horror games aren’t just about mechanics. They’re about mood. About crawling into your brain and setting up camp in the dark corners.

Whether you’re creeping through a haunted forest, decoding a cursed text adventure, or hiding from your screeching teammates in a cursed house—if you’re scared, you’re in it.

That’s horror.

And there’s a version out there with your name on it.

Leave a Reply